Overview

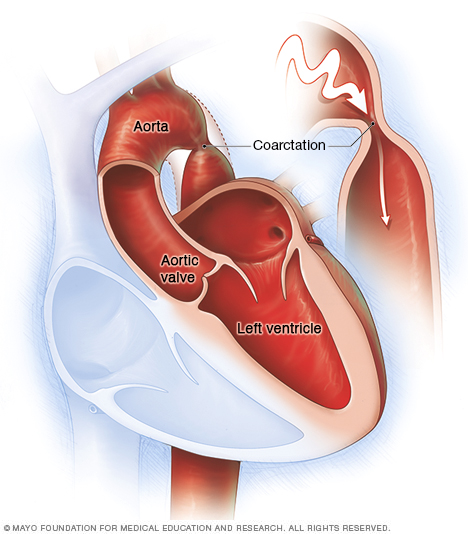

The aorta is the largest artery in the body. It moves oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body. Aortic coarctation (ko-ahrk-TAY-shun) is a narrowing of the aorta. It forces the heart to pump harder to move blood through the aorta.

Coarctation of the aorta is generally present at birth (congenital heart defect). Symptoms can range from mild to severe. The condition might not be detected until adulthood.

Coarctation of the aorta often occurs along with other congenital heart defects. Treatment is usually successful, but the condition requires careful lifelong follow-up.

Symptoms

Coarctation of the aorta symptoms depend on how much of the aorta is narrowed. Most people don't have symptoms. Mild coarctation may not be diagnosed until adulthood.

Babies with severe coarctation of the aorta may show symptoms shortly after birth. Symptoms of coarctation of the aorta in infants include:

- Difficulty breathing

- Difficulty feeding

- Heavy sweating

- Irritability

- Pale skin

Symptoms of coarctation of the aorta after infancy commonly include:

- Chest pain

- Headaches

- High blood pressure

- Leg cramps or cold feet

- Muscle weakness

- Nosebleeds

Depending on where the coarctation is located, blood pressure may be high in the arms and low in the legs and ankles.

Coarctation of the aorta often occurs with other heart defects. Other symptoms depend on the type of congenital heart defect.

When to see a doctor

Seek medical help if you or your child has the following symptoms:

- Severe chest pain

- Fainting

- Sudden shortness of breath

- Unexplained high blood pressure

A complete health checkup helps determine the cause. If you or your child has sudden, unexplained chest pain, seek emergency medical care.

Causes

The cause of coarctation of the aorta is unclear. The condition is generally a heart problem present at birth (congenital heart defect).

Rarely, coarctation of the aorta develops later in life. Conditions or events that can narrow the aorta and cause this condition include:

- Traumatic injury

- Severe hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis)

- Inflamed arteries (Takayasu arteritis)

Coarctation of the aorta can affect any part of the aorta, but it's most often located near a blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus. That blood vessel connects the left pulmonary artery to the aorta.

With coarctation of the aorta, the left lower heart chamber (left ventricle) works harder to pump blood through the narrowed aorta. As a result, blood pressure rises in the left ventricle. The wall of the left ventricle may become thick (hypertrophy).

Risk factors

Coarctation of the aorta is more common in males than in females. Having certain genetic conditions, such as Turner syndrome, also raises the risk of coarctation of the aorta.

Coarctation of the aorta often occurs along with other congenital heart defects. Heart conditions associated with coarctation include:

- Bicuspid aortic valve. The aortic valve separates the lower left chamber (left ventricle) of the heart from the aorta. A bicuspid aortic valve has two flaps (cusps) instead of the usual three. Many people with coarctation of the aorta have a bicuspid aortic valve.

- Subaortic stenosis. A narrowing of the area below the aortic valve blocks blood flow from the lower left heart chamber to the aorta.

- Patent ductus arteriosus. The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel that connects the left lung (pulmonary) artery to the aorta. When a baby is growing in the womb, this vessel lets blood go around the lungs. Shortly after birth, the ductus arteriosus usually closes. If it remains open, the opening is called a patent ductus arteriosus.

- Holes in the wall between the left and right sides of the heart. Some people are born with a hole in the heart wall (septum) between the upper chambers (atrial septal defect) or the lower chambers (ventricular septal defect).This causes oxygen-rich blood from the left side of the heart to mix with oxygen-poor blood in the right side of the heart.

- Congenital mitral valve stenosis. This is a heart valve problem present at birth. The mitral valve is between the upper and lower left heart chambers. It lets blood flow through the left side of the heart. In mitral valve stenosis, the valve is narrowed, reducing blood flow. Symptoms include shortness of breath, difficulty breathing during exercise and shortness of breath when lying flat.

Complications

Prompt treatment is needed to help prevent complications. Without treatment, coarctation of the aorta in babies may lead to heart failure or death.

Long-term (chronic) high blood pressure is the most common complication of coarctation of the aorta. Blood pressure usually drops after repair surgery. But it may still be higher than usual.

Other complications of coarctation of the aorta may include:

- A weakened or bulging artery in the brain (brain aneurysm)

- Bleeding in the brain (hemorrhage)

- Aortic rupture or tear (dissection)

- Enlargement in part of the aorta's wall (aneurysm)

- Premature narrowing of the blood vessels that supply the heart (coronary artery disease)

- Stroke

If the coarctation of the aorta is severe, the heart might not be able to pump enough blood to the other organs. This can cause heart damage. It may lead to kidney failure or other organ failure.

Complications are also possible after treatment for coarctation of the aorta. These include:

- Aorta re-narrowing (re-coarctation, possibly years after treatment)

- High blood pressure

- Aortic aneurysm or rupture

People with coarctation of the aorta need regular health checkups for life.

Prevention

There's no known way to prevent coarctation of the aorta. Early detection can help prevent complications. Talk to your health care provider if you or your child has a condition that increases the risk of aortic coarctation, such as Turner syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve or another heart defect. Also tell your provider if you have a family history of congenital heart disease.

Diagnosis

The age at which coarctation of the aorta is diagnosed depends on the severity of the condition. Severe aortic coarctation is usually diagnosed soon after birth. The condition may be seen with ultrasound during pregnancy.

Adults and older children with mild coarctation of the aorta may not have symptoms and may appear healthy. A health care provider checks for the following when making a diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta:

- High blood pressure in the arms

- A difference in blood pressure between the arms and legs — blood pressure in the legs is lower than blood pressure in the arms

- A weak or delayed pulse in the legs

- A whooshing sound caused by faster blood flow through the narrowed artery (heart murmur)

Tests

Tests to confirm a diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta may include:

- Echocardiogram. This test uses sound waves to create images of the heart in motion. An echocardiogram can often show the location and severity of aortic coarctation. It can also reveal other congenital heart defects, such as a bicuspid aortic valve. An echocardiogram is often used to diagnose coarctation of the aorta and guide treatment.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick and painless test measures the electrical activity of the heart. During an ECG, sensors (electrodes) are attached to the chest and sometimes to the arms or legs. Wires connect the sensors to a machine, which displays or prints results. If the coarctation of the aorta is severe, an ECG may show thickening of the walls of the lower heart chambers (ventricular hypertrophy).

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray creates images of the heart and lungs. A chest X-ray might show a narrowing in the aorta at the site of the coarctation or an enlarged section of the aorta or both.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the heart and blood vessels. It can show the location and severity of the coarctation of the aorta, damage to other blood vessels, and other heart defects. Your care provider may also use MRI results to guide treatment.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan uses a series of X-rays to create detailed cross-sectional images of the body.

- CT angiogram. A CT angiogram uses a dye and special X-rays to show how blood flows through the veins and arteries. The test can show the location and severity of coarctation of the aorta and determine whether it affects other blood vessels in your body. A CT angiogram can also be used to guide treatment.

-

Cardiac catheterization. This test helps reveal blockages in the heart arteries. A long, thin flexible tube (catheter) is inserted in a blood vessel, usually in the groin or wrist, and guided to the heart. Dye flows through the catheter to arteries in the heart. The dye helps the arteries show up more clearly on X-ray images and video.

Cardiac catheterization can help determine the severity of the aortic coarctation. Catheter procedures may also be used to perform certain treatments for coarctation of the aorta.

Treatment

Treatment for coarctation of the aorta depends on the age at the time of diagnosis and the severity of the condition. If there are other congenital heart defects, they may be repaired at the same time.

Treatment may include medications to control symptoms and procedures or surgery to repair the aorta.

Doctors trained in heart and blood vessel conditions (cardiologists), heart surgery (cardiovascular surgeons), and care providers trained in congenital heart disease help determine the most appropriate treatment for coarctation of the aorta.

Medication

Medication may be prescribed to control blood pressure before and, sometimes, after repair surgery. Although repairing aortic coarctation improves blood pressure, many people still need to take blood pressure drugs after a successful surgery or procedure.

Babies with severe coarctation of the aorta often are given a medication that keeps the ductus arteriosus open. This allows blood to flow around the narrowed area of the aorta until surgery is done.

Surgery or other procedures

There are several procedures and surgeries to repair aortic coarctation. Together, you and your health care team can discuss which type is most likely to be successful. Options include:

-

Balloon angioplasty and stenting. This may be the first treatment for aortic coarctation. Sometimes it's done if narrowing occurs again after coarctation surgery.

During balloon angioplasty, the doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube (catheter) into an artery in the groin. It's moved through the blood vessels to the heart using X-rays as a guide. An uninflated balloon is placed into the catheter and moved into the area of the narrowed aorta. The balloon is inflated. The inflated balloon widens the aorta, so blood flows more easily. Angioplasty is often combined with the placement of a small wire mesh tube called a stent. The stent helps keep the artery open, decreasing the chance of narrowing again.

- Resection with end-to-end anastomosis. This method involves removing the narrowed area of the aorta (resection) and then connecting the two healthy parts of the aorta (anastomosis).

- Subclavian flap aortoplasty. A part of the blood vessel that delivers blood to the left arm (left subclavian artery) might be used to expand the narrowed area of the aorta.

- Bypass graft repair. This surgery uses a tube called a graft to reroute blood around the narrowed area of the aorta.

- Patch aortoplasty. The surgeon cuts across the narrowed area of the aorta and then attaches a patch of synthetic material to widen the blood vessel. Patch aortoplasty is useful if the coarctation involves a long part of the aorta.

After aortic repair surgery, health checkups are needed for life to measure blood pressure and monitor for complications.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Follow these tips to help manage the condition and prevent future heart problems:

- Get regular exercise. Regular exercise helps lower blood pressure. Ask your provider about whether you have any activity restrictions. Some physical activities, such as weightlifting, can temporarily raise blood pressure. Your provider may do an exam and tests to determine if it's safe to lift weights or play competitive sports.

- Consider pregnancy carefully. Coarctation of the aorta, even after repair, may increase the risk of aortic rupture, aortic dissection or other complications during pregnancy and delivery. Before becoming pregnant, talk to your health care provider about the possible risks and complications. Together, you and your provider can discuss and plan for any special care needed during pregnancy. Careful management of blood pressure during pregnancy also is important.

- Prevent heart infections. Bacteria can affect the inner lining of the heart or valves, causing a condition called endocarditis. If you have endocarditis or any type of congenital heart disease, talk to your dentist and other care providers about your risks and whether you need preventive antibiotics.

Preparing for an appointment

If you or your child develops symptoms of coarctation of the aorta, call your health care provider. After the first exam, you or your child may be referred to a doctor trained in the diagnosis and treatment of heart conditions (cardiologist).

Here's some information to help you prepare for your appointment, and what to expect from your provider.

What you can do

- Write down any symptoms you or your child has had, and for how long.

- Write down important medical information, including any other health conditions.

- Make a list of all medications, vitamins and supplements that you or your child is taking. Include the doses.

- Ask a family member or friend to come with you to the appointment, if possible. Someone who goes with you can help remember what the doctor says.

- Write down the questions you want to be sure to ask your provider.

Questions to ask the provider at the first appointment include:

- What is likely causing these symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes for these symptoms?

- What tests are needed?

- Should a specialist be consulted?

Questions to ask if you're referred to a cardiologist include:

- How severe is the coarctation of the aorta?

- Did tests reveal any other heart defects?

- What is the risk of complications from coarctation of the aorta?

- What treatment do you recommend?

- If you're recommending medications, what are the possible side effects?

- If you're recommending surgery, what type of procedure is most likely to be successful and why?

- What will be involved in recovery and rehabilitation after surgery?

- How often should my child or I be seen for follow-up exams and tests?

- What symptoms should I watch for at home?

- What is the long-term outlook for this condition?

- Do you recommend any dietary or activity restrictions?

- Are antibiotics needed before dental appointments or other medical procedures?

- Is pregnancy safe for those with coarctation of the aorta?

- What is the risk that my or my child's future children will have this defect?

- Should I meet with a genetic counselor?

Don't hesitate to ask your provider any other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

The health care provider will examine you or your child and ask several questions.

If you have coarctation of the aorta, the provider may ask:

- What are your symptoms?

- When did the symptoms start?

- Have the symptoms gotten worse over time?

- Does exercise or activity make your symptoms worse?

- Have you been diagnosed with any other medical conditions?

- What medications are you currently taking, including those bought without a prescription and vitamins and supplements?

- Do you have a family history of heart problems?

- Do you or did you smoke? How much?

- Do you have any children?

- Are you planning to become pregnant in the future?

If your baby or child is affected, the provider may ask:

- What are your child's symptoms?

- When did you first notice these symptoms?

- Is your child gaining weight at a normal rate?

- Does your child have any breathing problems, such as running out of breath easily or breathing rapidly?

- Does your child tire easily?

- Does your child sweat heavily?

- Does your child seem irritable?

- Do your child's symptoms include chest pain?

- Does your child often have cold feet?

- Has your child been diagnosed with any other medical conditions?

- Is your child currently taking any medications?

- Is there a history of heart problems or congenital heart defects in your child's family?

© 1998-2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use