Overview

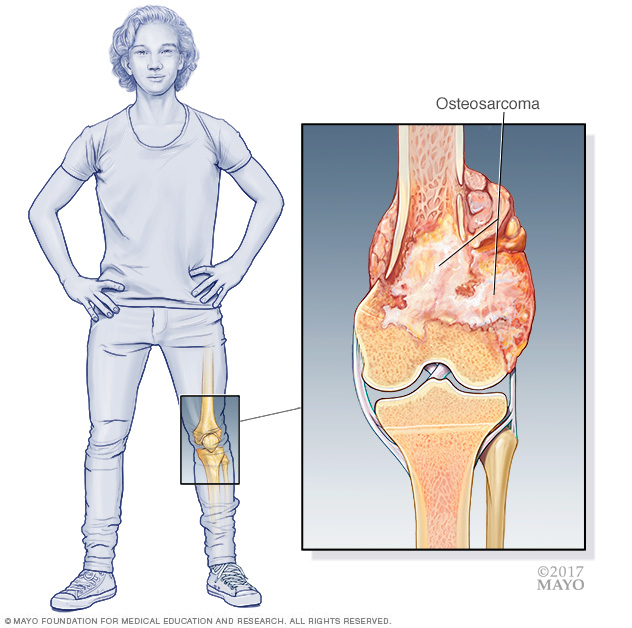

Osteosarcoma is a kind of cancer that begins in the cells that form bones. Osteosarcoma tends to happen most often in teenagers and young adults. But it also can happen in younger children and older adults.

Osteosarcoma can start in any bone. It's most often found in the long bones of the legs, and sometimes the arms. Very rarely, it happens in soft tissue outside the bone.

Advances in the treatment of osteosarcoma have improved the outlook for this cancer. After treatment for osteosarcoma, people sometimes face late effects from the strong treatments used to control the cancer. Healthcare professionals often suggest lifelong monitoring for side effects after treatment.

Symptoms

Osteosarcoma signs and symptoms most often start in a bone. The cancer most often affects the long bones of the legs, and sometimes the arms. The most common symptoms include:

- Bone or joint pain. Pain might come and go at first. It can be mistaken for growing pains.

- Pain related to a bone that breaks for no clear reason.

- Swelling near a bone.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with a healthcare professional if you or your child has ongoing symptoms that worry you. Osteosarcoma symptoms are like those of many more common conditions, such as sports injuries. The health professional might check for those causes first.

Causes

It's not clear what causes osteosarcoma.

Osteosarcoma happens when bone cells develop changes in their DNA. A cell's DNA holds the instructions, called genes, that tell a cell what to do. In healthy cells, the DNA gives instructions to grow and multiply at a set rate. The instructions tell the cells to die at a set time.

In cancer cells, the DNA changes give different instructions. The changes tell the cancer cells to make many more cells quickly. Cancer cells can keep living when healthy cells would die. This causes too many cells.

The cancer cells might form a mass called a tumor. The tumor can grow to invade and destroy healthy body tissue. In time, cancer cells can break away and spread to other parts of the body. When cancer spreads, it's called metastatic cancer.

Risk factors

Most people with osteosarcoma don't have any known risk factors for the cancer. But these factors can increase the risk of osteosarcoma:

- Certain conditions that run in families. These include hereditary retinoblastoma, Bloom syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome and Werner syndrome.

- Other bone conditions. These include Paget's disease of bone and fibrous dysplasia.

- Prior treatment with radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

There is no way to prevent osteosarcoma.

Complications

Complications of osteosarcoma and its treatment include the following.

Cancer that spreads, also called metastasizes

Osteosarcoma can spread from where it started to other areas. This makes treatment and recovery harder. Osteosarcoma most often spreads to the lungs, the same bone or another bone.

Coping after surgery to remove an arm or leg

Surgeons aim to remove the cancer and spare the arm or leg when they can. But sometimes surgeons need to remove part of the affected limb to remove all the cancer. Learning to use an artificial limb, called a prosthesis, takes time, practice and patience. Experts can help.

Long-term treatment side effects

The strong treatments needed to control osteosarcoma can cause major side effects, both in the short and long term. Your healthcare team can help you or your child manage the side effects that happen during treatment. The team also can give you a list of side effects to watch for in the years after treatment.

Diagnosis

Osteosarcoma diagnosis may begin with a physical exam. Based on the findings of the exam, there might other tests and procedures.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests make pictures of the body. They can show the location and size of an osteosarcoma. Tests might include:

- X-ray.

- MRI.

- CT.

- Bone scan.

- Positron emission tomography scan, also called a PET scan.

Removing a sample of cells for testing, called a biopsy

A biopsy is a procedure to remove a sample of tissue for testing in a lab. The tissue might be removed using a needle that is put through the skin and into the cancer. Sometimes surgery is needed to get the tissue sample. The sample is tested in a lab to see if it is cancer. Other special tests give more details about the cancer cells. Your healthcare team uses this information to make a treatment plan.

Determining the type of biopsy needed and how it should be done requires careful planning by the medical team. The biopsy needs to be done so that it won't get in the way of future surgery to remove the cancer. Before having a biopsy, ask your healthcare professional to refer you to a team of experts who have experience treating osteosarcoma.

Treatment

Osteosarcoma treatment most often involves surgery and chemotherapy. Rarely, radiation therapy also might be an option if the cancer can't be treated with surgery.

Surgery

The goal of surgery is to remove all the cancer cells. In planning the surgery, the healthcare team keeps in mind how the surgery will affect your or your child's daily life. The extent of surgery for osteosarcoma depends on several factors, such as the size of the cancer and where it is.

Operations used to treat osteosarcoma include:

-

Surgery to remove the cancer only, also called limb-sparing surgery. Most osteosarcoma operations can be done in a way that removes all the cancer and spares the arm or leg. Whether this type of surgery is an option depends, in part, on the extent of the cancer and how much muscle and tissue need to be removed.

If a section of bone is removed, the surgeon will rebuild the bone. How the bone is rebuilt depends on the situation. Options include metal implants or bone grafts.

- Surgery to remove the affected arm or leg, also called amputation. Rarely a surgeon might remove the affected leg or arm to get all the cancer. After surgery, an artificial arm or leg can be used. This is called a prosthesis.

-

Surgery to remove the lower portion of the leg, also called rotationplasty. Rotationplasty might be an option for osteosarcoma in and around the knee joint. In this surgery, the surgeon removes the cancer and surrounding area, including the knee joint. The foot and ankle are then rotated and put backward on the part of the leg that remains above the knee. The ankle then works as a knee.

A prosthesis is used for the lower leg and foot. This surgery is sometimes a good option for children who are still growing. It allows them to take part in sports and physical activities.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy treats cancer with strong medicines.

For osteosarcoma, chemotherapy often is used before surgery. It can shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove.

After surgery, chemotherapy treatments might be used to kill any cancer cells that might remain.

For osteosarcoma that returns after surgery or spreads to other areas of the body, chemotherapy might help relieve pain and slow the growth of the cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy treats cancer with powerful energy beams. The energy can come from X-rays, protons or other sources. During radiation therapy, you lie on a table while a machine moves around your body. The machine directs radiation to precise points on your body.

Radiation is not often used to treat osteosarcoma. Radiation therapy might be suggested instead of surgery if surgery can't remove all the cancer.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are studies of new treatments. These studies provide a chance to try the latest treatments. The risk of side effects might not be known. Ask your healthcare team if you or your child might be able to be in a clinical trial.

Coping and support

A diagnosis of osteosarcoma can feel overwhelming. With time you'll find ways to cope with the distress and uncertainty of cancer. Until then, you might find the following helpful:

Learn enough about osteosarcoma to make decisions about care

Ask your or your child's healthcare professional about osteosarcoma, including treatment options. As you learn more, you may feel better about making choices about treatment options. If your child has cancer, ask the healthcare team to guide you in talking to your child about the cancer in a caring way that your child can understand.

Keep friends and family close

Keeping your close relationships strong will help you deal with osteosarcoma. Friends and family can help with daily tasks, such as helping take care of your home if your child is in the hospital. And they can serve as emotional support when you feel like you're dealing with more than you can handle.

Ask about mental health support

Talking to a counselor, medical social worker, psychologist or other mental health professional also may help. Ask your healthcare team for options for professional mental health support for you and your child. You also can check online for a cancer organization, such as the American Cancer Society, that lists support services.

Preparing for an appointment

If there are signs and symptoms that worry you, start by making an appointment with a healthcare professional. If the health professional suspects osteosarcoma, ask to be referred to an experienced specialist.

Osteosarcoma typically needs to be treated by a team of specialists, which may include, for example:

- Orthopedic surgeons who specialize in operating on cancers that affect the bones, called orthopedic oncologists.

- Other surgeons, such as pediatric surgeons. The type of surgeons depends on the site of the cancer and the age of the person with osteosarcoma.

- Doctors who specialize in treating cancer with chemotherapy or other systemic medicines. These might include medical oncologists or, for children, pediatric oncologists.

- Doctors who study tissue to diagnose the specific type of cancer, called pathologists.

- Rehabilitation specialists who can help in recovery after surgery.

What you can do

Before the appointment, make a list of:

- Signs and symptoms, including any that seem unrelated to the reason for the appointment, and when they began.

- Any medicines you or your child takes, including vitamins and herbs, and their doses.

- Key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

Also:

- Bring scans or X-rays, both the images and the reports, and any other medical records that are linked to this condition.

- Make a list of questions to ask the health professional to make sure you get the information you need.

- Tak a relative or friend to the appointment, if you can, to help you remember the information you get.

For you or your child, your questions might include:

- What type of cancer is this?

- Has the cancer spread?

- Are more tests needed?

- What are the treatment options?

- What are the chances that treatment will cure this cancer?

- What are the side effects and risks of each treatment option?

- Which treatment do you think is best?

- Will treatment affect being able to have children? If so, do you offer ways to preserve that ability?

- Are there brochures or other printed material I can have? What websites do you suggest?

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional will likely ask you questions, such as:

- What are the signs and symptoms that worry you?

- When did you notice these symptoms?

- Do you always have the symptoms, or do they come and go?

- How severe are the symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve the symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen the symptoms?

- Is there a personal or family history of cancer?

© 1998-2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use